The structural organization and properties of cell membranes are set by their molecular components: lipids, proteins and carbohydrates. Lipids are essential for membranes because they organize in lipid bi-layers, i.e., cellular membranes, and they can modulate membrane properties in many ways since there are more than 1000 different lipid species in eukaryote membranes. Lipids are in charge of physical features of membranes. Length and saturation of their fatty acid chains regulate fluidity and thickness of membranes. The uneven distribution between the two lipid hemilayers generates membrane asymmetry. Electrical charges located in the hydrophilic lipid heads contribute to the electrochemical gradient between both membrane surfaces, modulating the electrochemical membrane potential. Through lateral interactions, lipids can modulate the activity of membrane proteins. The lateral heterogeneity of cell membranes are thought to be caused by lateral lipid-lipid interactions, forming spatial and functional domains that contain higher proportions of certain types of lipids and proteins. These regions are known as lipid rafts or membrane domains. Furthermore, lipids may work as second messengers, leaving membranes and diffusing to intracellular compartments to trigger cellular responses.

membrane

models

Lipids make up around 50 % of the plasma membrane weight, with about 5 million lipids per µm2 of membrane. There are more than 1000 types of lipids distributed through the different membranes of a eukaryotic cell, with specific proportions depending on the membrane. It is thought that about 5 % of the genes of a cell are related to lipid synthesis.

Membrane lipids show a hydrophobic domain toward the inner part of the membrane and a hydrophilic domain toward the aqueous environment. The hydrophilic domains are the two membrane surfaces. That is why they are known as amphiphilic. There are three mayor groups of membrane lipids regarding their structure and molecular composition: glycerophospholipids (also known as glycerolipids, phosphoglycerides or simply phospholipids), sphingolipids and sterols.

1. Glycerophospholipids or phosphoglycerides

Glycerophospholipids are the most abundant type of lipids in cell membranes, they acount for more than 70 % of membrane lipids. Structurally, they have 3 components: two fatty acid chains, glycerol, and phosphoric acid. Other molecules bind to the phosphoric acid, providing lipid diversity (Figure 1). Fatty acid chains are 13 to 19 carbon atoms in length. Most carbon-carbon bonds are simple, which are referred to as saturated bonds. However, more than half of the fatty acids contain at least one double carbon-carbon bond, which is referred to as unsaturated. Each double bond makes a permanent bend in the fatty acid chain and, although rotation of these chains is restricted, the increase of unsaturated fatty acids makes membranes more fluid because lipids are more separated to one another. Fatty acids constitute the inner hydrophobic (water phobia or water flee) part of membranes.

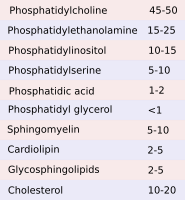

Glycerol links the two fatty acid chains to a phosphoric acid of the polar part or head. In the head, the phosphoric acid is also linked to a wide variety of molecules like ethanolamine, choline, serine, glycerol, inositol, or inositol 4,5-bi-phosphate, that produces the different species of glycerophospholipids. The names of the different glycerophospholipids derive from these molecules. For example, phosphatidylcholine accounts for more than 50 % of the lipids of the eukaryote membranes.

2. Sphingolipids

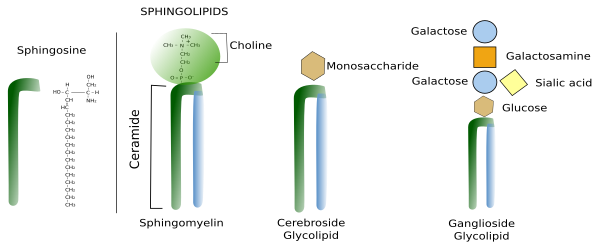

Sphingolipids contain a molecule of sphingosine, which is a nitrogenated alcohol with a long carbon chain. Sphongosines binds a fatty acid chain to form a molecule known as ceramide (Figure 2. See also ↗ ). Diverse polar heads can be linked to ceramide. In this way, sphingolipids show a molecular structure similar to glycerophospholipids: two hydrophobic chains linked to a hydrophilic head. Most membrane glycolipids in animal cell membranes, which are those containing sugar in the hydrophilic domain, are sphingolipids. Sphingomyelin, other type of sphingolipid, contains one ethanolamine or one phosphorylated choline in the hydrophilic head. Sphingolipids are more abundant in the plasma membrane than in organelles, and are proposed, together with cholesterol, as main players in the lateral segregation of membrane molecules into domains such as lipid rafts.

3. Sterols

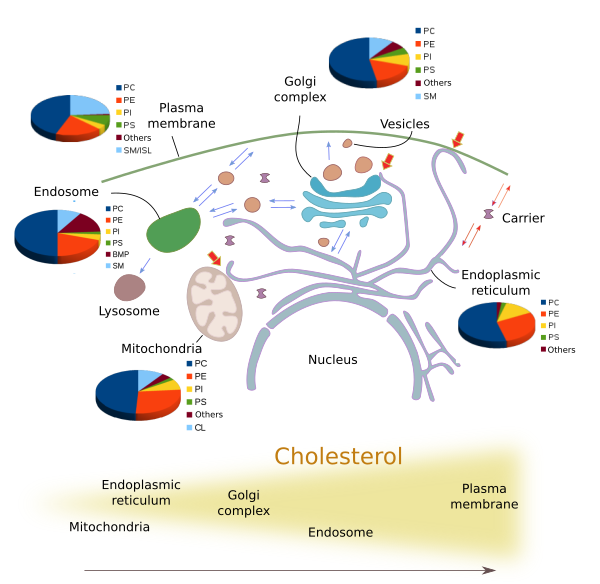

Cholesterol (Figure 3) is the most important sterol in animal cell membranes and the third most abundant type of lipid in the plasma membrane (up to 25 % of the total lipids) of animal cells, whereas it is scarce in membranes of organelles like endoplasmic reticulum (about 1 % of the total lipids), mitochondria and lysosomes. Cholesterol is not present in plant cell membranes, in some unicellular eukaryotes, nor in bacteria. However, these cells bear other types of sterols in their membranes. Sterols are essential for the integrity and functions of eukaryotic plasma membranes. They influence fluidity, stiffness and permeability of membranes. Moreover, it may modulate the activity of GPCR (G protein-coupled receptors), signal transduction and vesicular traffic. Cholesterol is located among the fatty acid chains of other lipids. It is important for the organization of membranes, particularly the plasma membrane, because, together with sphingolipids, contributes to create lateral membrane domains. It also participates in metabolic processes such us the synthesis of steroid hormones and bile salts.

4. Lipid distribution in cell membranes

Although there are three main types of membrane lipids, many different species of lipids are distinctly distributed through the eukaryotic membranes (Figures 4 and 5). The lipid composition varies in the different membranes of the cell. The identity of membrane bond organelles is determined by their molecules in their membranes, both lipids and proteins. For example, plasma membrane shows a different lipid composition than those of the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi complex. These differences are maintained even under a constant flux of lipids from the synthesis compartments, mainly the endoplasmic reticulum, through the Golgi complex towards other membranes, such as plasma membrane and endosome membranes. Vesicles, transporters and membrane-membrane contacts make possible the lipid flux between different membranes.

The amount and proportion of lipid species vary in the different cell membranes (Figure 5). For example, all membranes contain phosphatidylcholine, but this lipid type is more abundant in the endoplasmic reticulum membranes. In post-Golgi membranes, i.e., plasma membrane and endosomes, the proportion of sphingolipids and cholesterol is much higher than in the endoplasmic reticulum and the cis domain of the Golgi complex. Mitochondria, besides other common lipids, contain cardiolipin and phosphatidylglycerol as characteristic lipids synthesized by mitochondria themselves.

It means that there must be mechanisms to differentially distribute the species of lipids through the wide variety of membranes of the cell. Several molecular mechanisms have been proposed for this uneven distribution of lipids:

Lipid synthesis. The proportion of some lipids is determined by the place they are synthesized. For instance, sphingolipids are assembled in the Golgi complex and therefore are the post-Golgi compartments where these lipids are more abundant, and they are hardly found in the endoplasmic reticulum. In the same way, phosphatidylcholine is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum, where it is most abundant. However, this is not a general rule. For example, cholesterol is synthesized in the endoplasmic reticulum, but the amount of cholesterol is higher in post-Golgi membranes because it is quickly transported by vesicular traffic from the endoplasmic reticulum to other compartments. Furthermore, some lipids may be synthesized by chemical modifications of other type of lipids. Then, at the same time that a lipid is synthesized, another lipid disappears in the same membrane. In this way, the enzymes working locally can change the proportion of lipids in a particular compartment.

Selective transport. Lipids cannot travel freely through the cytosol because of their hydrophobic fatty chain. Whatever the transport mechanism, it can select the lipid types to be carried, therefore changing the population of lipids in both the source and the target membrane. The bulk transport of lipids in the cell is mostly by vesicles, that carry the lipids as components of their own membranes. For example, the vesicles budding from the trans domain of the Golgi complex toward the plasma membrane and endosomes are enriched in sphingolipids and cholesterol, when compared with the concentration of these lipids in the Golgi complex membranes. There are also proteins that can transfer single lipid molecules between membranes. They take a lipid from the source membrane, hide the fatty acid from the aqueous environment in the cytosol, and insert the lipid in the target membrane.

Membrane contact sites. At electron microscopy, membranes from different organelles can be observed very close to each other. There are proteins located between these membranes at the contact sites that transfer lipids between the two membranes, and therefore between the two organelles. Membrane contact sites involve organelles that are not directly communicated by vesicles, like endoplasmic reticulum and plasma membrane, or endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. There are also juxtaposed membranes of organelles directly connected by vesicles, like the endoplasmic reticulum and the trans domain of the Golgi complex, where the CERT (ceramide transfer protein) moves ceramide from the endoplasmic reticulum membranes to the trans Golgi network membranes.

Differential degradation and recycling of lipids. All membranes are under a heavy turnover of lipids, either by lipid degradation in situ or by taking them out in vesicles or transporters. Particular lipid species may be selected by both mechanisms, therefore influencing the ratio of lipid types in the membrane.

5. Asymmetry

Membrane asymmetry is the differential distribution of lipids between the two lipid hemilayers of the membrane. Whereas both hemilayers of the endoplasmic reticulum membrane show nearly the same lipid composition, but not entirely equal, membranes of the Golgi complex trans domain, and post-Golgi compartments, have quite different composition when comparing both hemilayers. Learn more about membrane asymmetry ↗.

-

Bibliography ↷

-

Bibliography

Bissig C, Gruenberg J. 2013. Lipid sorting and multivesicular endosome biogenesis. Cold Spring Harbour perspectives in biology. 5:a016816.

Janmey PA, Kinnunen PKJ. 2006. Byophisical properties of lipids and dynamic membranes. Trends in cell biology. 16:538-546.

Vance JE. 2015. Phospholipid synthesis and transport in mammalian cells. Traffic. 16:1.

van Meer G, Voelker DR, Feigenson GW. 2008. Membrane lipids: where are they a how they behave. Nature reviews in molecular cell biology. 9:112-124.

-

Cell membrane

Cell membrane