1. Structure

2. Instability

3. MAPs

4. Motor proteins

5. MTOCs

6. Functions

- Organization

- Cilia / flagela

Microtubules are a component of the cytoskeleton involved in the internal organization of eukaryote cells. They carry out many functions. Thus, they contribute to the spatial organization of organelles, work as tracks for vesicular trafficking, are needed during cell division by forming the mitotic spindle, participate in cell movement, contribute to cell polarization in some cell types, and are an essential component of cilia and flagella.

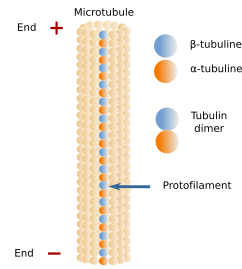

1. Structure

Microtubules are long and relatively stiff tubules (Figures 1 and 3). Their walls are made up of many dimers of globular proteins: α- and β-tubulin (Figure 2), which are lined up in long rows known as protofilaments. Within a protofilament, there are no chemical bonds between adjoining tubulin dimers, but they are attached by electrical forces. A microtubule is usually composed of 13 protofilaments. α- and β-tubulin dimers are oriented in the same way, so that there is always α-tubulin of the first dimer at one end of the protofilament and β-tubulin of the last dimer at the other end. All protofilments in a microtubule are oriented in the same way. It means that microtubules are polarized structures. The end formed by α-tubulins is known as minus end, and the end formed by β-tubulins is known as the plus end. New tubulin dimers are mainly added to the plus end, where the growth of the microtubule usually happens, although depolymerization also occurs. In the minus end, depolymerization prevails over polymerization.

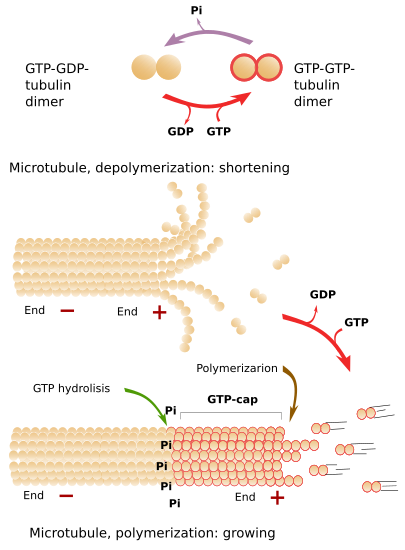

2. Dynamic instability

Microtubules are highly dynamic structures, continuously undergoing polymerization and depolymerization, mainly happening at the plus end. There is a steady exchange of tubulin dimers between the cytosol and microtubules. In a typical fibroblast, half of the available tubulin is free in the cytosol, and the other half forms part of microtubules. The addition of new tubulin dimers to the plus end makes the microtubule grow in length. The growth is stopped from time to time, and growth periods alternate with shrinkage periods. Depolymerization is sometimes so strong that the complete microtubule may disappear. However, it is more frequent a new polymerization (growing) period. The alternation between polymerization and depolymerization of microtubules is known as dynamic instability.

Free tubulin dimers are linked to two GTP molecules (Figure 4). Some time later, after the joining of a tubulin dimer to the plus end of a microtubule, one GTP is hydrolyzed to ADP. If the rate of adding GTP-GTP-tubulin dimers to the plus end is faster than the hydrolysis rate, there will always be a group of tubulin dimers with GTP-GTP in the plus end, which is known as GTP-cap. GTP-cap stabilizes the plus end of the microtubule and boosts polymerization. If the addition rate of new GTP-GTP-tubulin dimers is low, the hydrolysis rate may overcome the polymerization speed. This means that there are GTP-GDP-tubulin dimers at the plus end, which makes protofilaments weakly adhere to one another. In this situation, massive depolymerization starts. If the plus end is stabilized by external elements, the microtubule grows again (Figure 4). GTP-ADP-tubulin dimers released to the cytosol and quickly phosphorylated to GTP-GTP-tubulin dimers, which are ready to join a microtubule plus end.

3. MAPs

Microtubules do not directly interact much with other cell structures. However, there are microtubules associated proteins (MAPs) controlling the organization, stability, growth, and other aspects of microtubule behavior. MAPs may interact with the microtubule plus end affecting the dynamic instability, either by boosting grow or depolymerization. Katanin develops a more drastic action because it breaks the microtubules down. MAPs also allow microtubules to interact with other cellular elements, such as organelles or cytosolic molecules, such as other cytoskeleton components. Some substances that affect polymerization or depolymerization of microtubules have been used as medicines. For example, colchicine inhibits microtubule growth, whereas taxol strongly attachs to microtubules, preventing depolymerization.

4. Motor proteins

There are proteins that can get attached to microtubules and move either toward the plus end or the minus end. They are known as motor proteins. Dyneins and kinesins are the two motor protein families. Dyneins move toward the minus end of the microtubule, and kinesins toward the plus end. Both comprise a globular region that binds ATP and interacts with the microtubule, and a tail domain that recognizes and binds the cargo to be transported. ATP hydrolysis in the globular domain changes the molecular conformation and makes the protein moves along the microtubule.

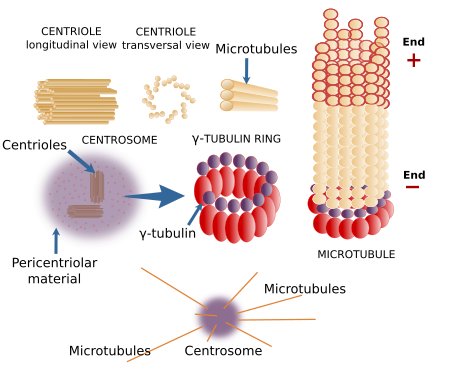

5. MTOCs

The concentration of cytosolic tubulin dimers is not high enough to spontaneously polymerizes into new microtubules. In the cell, there are molecular structures known as microtubule organizing centers (MTOCs), where microtubules are nucleated. The minus end of the new microtubule is usually anchored to the MTOC, whereas the plus end grows the microtubule through the cytosol. Rings of γ-tubulin, located at the MOTCs, are molecular complexes that work as templates for the nucleation of new microtubules. Other proteins, such as TPX2 and XMAP125 also contribute to the formation of new microtubules.

The centrosome is the major MTOC in animal cells (Figure 5). It is the main responsible for the number, localization and spatial organization of microtubules. In most animal cells, during the G1 and G0 phases of the cell cycle, there is one centrosome per cell found near the nucleus. However, megakaryocytes contains multiple centrosomes, and muscle fibers lack centrosomes. The centrosome consists of two components: a couple of orthogonally oriented centrioles and a surrounding pericentriolar material. Each centriole is a cylindrical structure with a wall made up of 9 triplets of microtubules.

There are many γ-tubulin molecules in the pericentriolar material arranged in rings, known as γ-tubulin rings, that nucleate microtubules. Centrioles, however, do not participate in the formation of microtubules nor in their spatial orientation, excepting the distal and subdistal appendages, which are structures attached to the mature centriole that can nucleate microtubules. The function of centrioles is still unknown. For example, plant cells lack centrioles, but they can segregate chromosomes, divide into two new cells, and organize their microtubules without any problem. Centrioles are similar to basal bodies, structures located in the basal part of the cilia and flagella.

The centrosome is also important during the cell cycle because it contains many proteins involved in the progress of the cell cycle and in the organization of the mitotic spindle. For example, duplication of the centrosome before mitosis of animal cells is essential to produce two "healthy" new cells.

There are other cellular places where microtubules can be nucleated. Blepharoplasts are molecular complexes found in plant cells and in some animal cells that can nucleate microtubules, and sometimes they can also form centrioles and centrosomes. Plant cells lack centrioles and do not form typical centrosomes, but they have γ-tubulin rings associated with the nuclear envelope, blepharoplasts, and are scattered through the cytoplasm. Plant cells nucleate microtubules more frequently in the peripheral cytoplasm. The main MTOC in yeasts is the polar body, which is inserted into the nuclear envelope. There are other microtubule nucleators such as chromosomes, which can form a mitotic spindle without centrosomes. The cisterns of the Golgi apparatus nucleate microtubules that help to maintain the general organization of the organelle.

6. Function

Intracellular organization

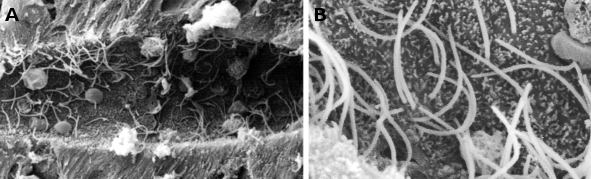

Microtubules are classified into two types: stable microtubules, found in cilia and flagella, and dynamic microtubules, found in the cytosol (Figure 6). Cytosolic microtubules, besides their role in the mitotic spindle formation and chromosome segregation, are also involved in the internal movement of organelles such as mitochondria, lysosomes, pigment inclusions, lipid drops, etcetera. They are also needed for vesicular trafficking. When cells in culture are observed at light microscopy, organelles show an alternation between quick movement and quiet periods. This behavior, known as saltatory movement, occurs when organelles are moving along the microtubules. Cytosolic microtubules are also involved in the shape and location of some organelles, such as the Golgi complex and endoplasmic reticulum. The addition of colchicine depolymerizes the microtubular system of the cell, and both organelles collapse and divide into small vesicles scattered through the cytoplasm. When colchicine is removed and microtubule repolymerization is allowed, both organelles get back to the typical morphology and cellular localization. Organelles and vesicles are propelled along microtubules by motor proteins.

In plant cells, most intracellular movements rely on actin filaments. Microtubules are distributed in the peripheral cytoplasm (Figure 6), where they influence the orientation of the cellulose fibers of the cell wall and determines the growth and mechanical resistance of the cell.

Cilia and flagella

Cilia and flagella are cellular structures protruding from the cell surface, contain microtubules, and are delimited by the plasma membrane. Cells use cilia and flagella to move the surrounding liquid, to move themselves if they are free cells, or as sensory structures. Cilia are shorter than flagell and more numerous, and their movements propel the liquid parallel to the cell surface. Flagella move the surrounding liquid perpendicularly to the cell surface.

Cilia and flagella are complex structures made up of more than 250 different proteins (Figures 7 and 8). Both have a central structure of microtubules known as axoneme. The axoneme is composed of 9 outer pairs of microtubules, plus a central pair of microtubules. This organization is written down as 9x2+2. The axoneme grows from the basal body, which has 9 triplets of microtubules (9x3+0). The outer pairs of microtubules of the axoneme are connected to each other by nexin proteins, whereas protein spokes connect the outer pairs with the central pair. The motor protein dynein is located between the outer pairs. Dynein is involved in the movement of cilia and flagella.

Some types of cilia are known as primary cilia. Primary cilia lack the central pair of microtubules, cannot move, are scarce, and sometimes appear alone in the cells. At least one cilium is present in most animal cells studied so far. Primary cilia bear in their membranes many receptors and ionic channels, so that a sensory role has been suggested.

Actin filaments

Actin filaments